New discoveries or the relentless display of craft?

An individual's aesthetic wiring directly relates to their choice of camera types when it comes to photographing what we might call their vision. I would argue that there is a spectrum between pure documentation of the subject matter, divorced from technical considerations of presentation, and the other extreme; the exercise of technical virtuosity which would consist of the highest level of craftsmanship.

At each extreme point of the spectrum either the lack of desire to embrace technology, or the wholesale embrace of technology, becomes an impediment to the most effective presentation of a subject --- or a visual idea.

In less extreme examples we can see how this bifurcation of intention in photography; the pure documentation versus the value of craft over context, drives the choice of tools individual artists embrace in order to bring their vision to fruition.

In thinking about those whose focus is to document an event, a person, a scene, etc. with respect for the content and the energy of the image I would put up as examples photographers such as Willian Klein and Robert Frank. In the opposite camp; those to whom craftsmanship and mastery seem to be more important than subject I would point to landscape photographer, John Sexton and supposed documentarian, Stephen Shore.

In their time both Klein and Frank selected cameras

not for their ultimate image quality but for their fluid nature and their transparency in terms of getting an image on film interpreted only by their selection of the moment of capture and the selection of an almost reactive composition. In an age where the standard camera format of commerce was the 4x5 inch camera, and a medium format twin lens camera was considered to be a

snapshot camera, these two artists (and others such as Henri-Cartier Bresson) chose to work with the (then) tiny 35mm cameras made by Leica, and then added insult to injury (in the eyes of their generation of photographers) by using fast, grainy, less sharp black and white films.

Their images all have an immediacy that allows us to more directly connect with the objects of their observation. Once the images were captured the images were printed in more or less direct methods. While the printers may have cropped slightly or burned and dodged a bit there was nothing like the wholesale manipulation of images that we routinely see in contemporary post processing where many times the captured image is a vague chimera that will be added to and massaged endlessly by today's oppressively addictive software.

In my past role as a specialist lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin I used to take my advanced photography classes to the

Humanities Research Center to see actual prints from the HRC's vast collection. We would don on the white cotton gloves and sit around an expansive wooden table and personally handle and view the quintessential photographic work of the 20th century in its purest guise, as black and white prints (mostly in sizes from 8x10 to, at the largest, 11x14 inches).

I was always left cold by the pristine work of photographers such as Minor White or even Edward Weston while any number of works by Leica toting social documentarians could perk my interest (and appreciation for their clarity and speed of seeing).

In one session we were looking at a portfolio of prints of Henri-Cartier Bresson's work. One print was a larger version of a photograph of the Pope, in Vatican City, in a throng a people. A student pointed out that HCB had missed focus. The Pope was not in razor sharp focus. We all sat back and looked at the print for a while and decided that the moment captured (and the way it was caught) certainly outweighed the technical shortcoming of the camera's operation. To be in the right spot at the right time with a functioning camera was much more important than not having the photo at all. In retrospect I have been considering how that image would have worked in a smaller print. Something like a 6x9 inch image on an 8x10 inch sheet of paper. Would we have even noticed the slight softness of focus on the Pope or would the smaller size render the technical deficiency moot?

This always starts me thinking along the lines of

"What if HCB had used a bigger camera with a higher potential image quality?" Having shot with a small Leica, a Rollei twin lens, and 4x5 inch cameras I feel confident in saying that he made the right choice of camera and film for his vision and his immediate circumstances.

When I look at the work of Robert Frank I understand that, with the ability to use the camera almost without conscious thought, and with the discreet profile of the small, handheld camera, Frank was able to capture moments of social documentation that were so unguarded that we feel the emotion of the people in the moment instead of just the

study in sociology that most journalism-style photography presents.

While held in high regard by many I can't stomach the lifeless virtuosity of most large format nature photographers. They really tell us nothing about nature or our place within it; they only use their naturalistic subjects as foils for their own clinical vision. Their intention seems to be to find in nature scenes that they can use as a base canvas upon which to showcase their skills and technical mastery of otherworldly tonal control, contrast and arch preservation of detail. When their audiences see the work they respond to the way the artist's control glorifies the experience of viewing replicas of nature by providing an alternative representation of what is generally visually mundane in situ.

One imagines these large format artists marching through the chaos of the woods with a folding view camera, stout tripod and a backpack full of film holders, looking for a vignette that can be forcibly composed into a structure considered "harmonious" by the masses and then stolen from its colorful and chaotic place in nature into a black and white showcase of gloriously rendered detail and order, with all the contrast of a Japanese pen and ink image. There is no impression of timeliness or emotional reaction to their moment of discovery, no AHA!!! instead one feels the plodding nature of a researcher who leisurely sets up a camera and then, in a series of

investigations works around the subject more or less begging it to yield some meager measure of intrinsic magic to give even the meanest spark of life to the artist's experiment in technical perfection. As sensual as kissing a porcelain mask.

Since these artists have the time, and additionally live and die by the highest expression of technical mastery, their tools of choice are the 4x5 and 8x10 inch cameras and a selection of films with the finest grain and the highest resolution. The classic representation of detail being more important than the subject itself. But the "seeing" doesn't stop with the rigorous capture of the scenic-ly mundane it continues in the dark room with another bout of arduous perfectionism until the photograph is as much a manipulated reference as a purely photographic print. The value, according to curators, is in the artist's interpretation in the final print of the original scene, not in the power of the original scene itself.

Another way to look at all of this (at least in the eyes of the great audience of

every man) is that few people outside the small (and shrinking) world of educated artists and art historians see the value of abstract painting, action painting, and non-representational painting in general. The further paintings diverge from hard core realism the less appreciated they are by most audiences. The masses demand as much verisimilitude to reality in their paintings as can be wedged into them. In this way the virtuoso photo-realistic painters, as well as those painters who just happen to be very compulsive, are publicly adored (and quickly forgotten).

In the current field of photography we seem to have same kind of situation that existed in the 1950's and 1960's. The middle of the curve of photographers seems obsessed with the need for "perfect" digital cameras. They define "perfect" as the cameras that can most accurately reproduce the scene in front of the camera in terms of sharpness, resolution, contrast and overall color correctness. They are willing to spend many multiples more money over less well appointed cameras in order to get these camera attributes so that these photographers can dogmatically pursue the creation of a "perfect image".

While any camera today can make a beautiful, reasonably sized print, there is a mania to have the camera that will make the biggest print with the least noise and the widest dynamic range. The maniacal pursuit of technical perfection blinds many to the charms and virtues of alternate tools. While a Zeiss Otus 85mm lens might be the sharpest lens in the photo cosmos it's just one focal length. If an artist has an elastic (and more interesting) and expansive personal vision of reality that requires being able to switch angles of view with speed and agility then the Otus becomes an encumbrance to his/her vision. It may be that a camera with an almost endless range of angles of view helps bring his/her vision into existence.

A frail or aging photographer with a lively and unique vision may not be able to physically carry all the bits and pieces of the "perfect system" out in the field. The weight of "perfected progress" might hinder him or her from even leaving their home to engage in their art. But what if their vision could give birth to great work with a smaller, easier to handle camera and a small selection of good lenses? Would their work be less valid? See the work of Jan Saudek

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Saudek

When I look across so many arenas of photo sharing; from Instagram to Google+ and to some of the old standbys like Flickr I am generally much more drawn to images that display immediacy and authenticity than I am to cleverly contrived and technically flawless images that lack any sort of contextual soul. It's rare that an image from a Sony A7Rii or a Nikon D810 is revered in social media for its imaging qualities --- they are almost always "liked" and "favorited" for the angle of composition and insightful moment at which the subject is captured, or the subject's gesture or expression, not in the way the camera's noiseless purity is displayed. More often, these days, the most interesting work is coming from the least complex of cameras --- iPhones.

There is a giant cult within contemporary photography that ignores the human magic of storytelling and instead concentrates on trying to show

the essence of a boring thing because a certain type of subject is a more pliable canvas on which to demonstrate the camera operator's mastery and control of their special tool. Wouldn't it be so much more interesting if they had a story, beyond all their proficiency, to tell?

I would suggest to anyone who really wants to see better to practice actually seeing by putting the A7rii/D810/5Dsr in a drawer and rummaging around to find that old point and shoot from ten years ago. Something like a Canon G9 or some Coolpix or an early Sony RX100xxxxx. Put the camera in "P" mode and go looking for subject matter than

interests you for more than just its ability to serve as a canvas for your

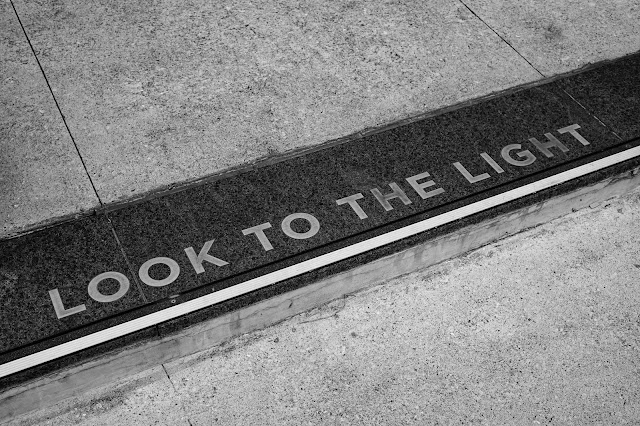

craftiness. Look for the beautiful smile of sensual person. Look for interesting clouds. React to a sweet expression. Consider a quickly fading gesture. Watch the light play across someone's elegant face. Find a moment that speaks to your sympathy for our shared existence. Reject easy opportunities just to show off your chops.

Turn off the review mechanism of the camera and just point the camera at things as they interest you, bring the camera to your eye and

click. You might just be amazed to find that if you stop contemplating perfection and start embracing serendipity, and the honest reactions of your emotional self, you may like the images that arise far more than the sterile work of proving your camera is a better artist than you.

Finally, I write about discovering scenes, gestures, etc. And of technologists also on a search for perfect foils for their art,

but there is another way. I consistently look back at the work of "constructionists" like Duane Michals whose work is neither

"discovered by happy accident" or the result of hours of arduous manipulation and obsessive control in the the darkroom --- after being captured by the "Best Camera in the World". Instead, he imagines and then directs photographic stories that resonate with so many audiences. His stories bubble up from his life. He constructs a visual narrative but without the artifice of perfectionism. It's a third way of seeing that we don't talk about enough. It's powerful and, reading the story of his career, you can see that the camera, or type of camera he uses, is unimportant. A minuscule part of his act of creation. Seems

imagination is one of the most powerful tools of all.

http://www.dcmooregallery.com/artists/duane-michals